At dawn, Father Evaristo, the priest of the Ching’ombe Mission, picked us up in Lusaka. Until a few days before this meeting, I didn’t know a single soul in Zambia. Now I was sitting in a pick-up truck with nine men on the way to Ching’ombe, a tiny, remote village in Central Zambia. I had originally planned an unspectacular two-week trip to Zambia with a few friends: the usual – National Parks, Livingstone, Victoria Falls. Well, it turned into an epic four-week journey by jeep, bus, train and ship to Zanzibar.

Natuleya – a Viennese NGO supports Ching’ombe

Shortly before I left for Zambia, I got to know William Giordani, founder of the small NGO Natuleya. He and his father have been supporting the mission in Ching’ombe, where William grew up to Italian parents, ever since. He always returns with his father for several weeks – this is how a school building was built, the mission’s power supply was provided (by a small hydroelectric power plant on the river) and a women’s workshop. There have recently been solar panels on the roof of the school, providing light in the dark classrooms – thanks to the Viennese company Haude .

William sent 3,000 Euros in donations with me to Zambia to pay for Constavius’ prosthetic leg. For the young man from Ching’ombe, a mistreated snake bite ended tragically – his lower leg had to be amputated.

I met Constavius in Lusaka, where he had been waiting for weeks for the prosthesis at a relative’s home. I offered to finance his trip home to Ching’ombe and accompany him to the village. Public transport does not reach the village; only off-road vehicles can cover the last 60km.

Hell of a ride to Ching’ombe with the Proud Sons of the Valley

The journey from Lusaka to Ching’ombe took 13 hours, partly because we were constantly collecting people, food, old clothes and tools. With me on the truck were Joseph, Cornellius and Raymond, long-time friends of William. The people in the village refer to them as “The Proud Sons of the Valley” who have made it, have good jobs in the capital and continue to actively support Ching’ombe.

When we stopped at a fast food restaurant for lunch, I sat down at a table, but Joseph said we’d eat outside, his friends would feel more comfortable eating lunch outside. A first taste of how different rural Africa can be. As we passed a small town, a man got on, who turned out to be Father Evaristo’s mechanic. When I asked why he didn’t come with him to Lusaka, Evaristo replied that the city was too big and scary for him, so he waited in this small town for the return journey.

For long stretches we drove on wide, well-maintained sandy roads, built and taken care off by Chinese companies. What will happen to these roads when the contract for road maintenance expires, nobody knows.

Darkness caught us on the infamous last 60 km. Father Evaristo raced in complete darkness along a track that off-road vehicles had plowed into the bush over the years. We all were thrown around and I wondered how long even a sturdy jeep could withstand such stress. During the turbulent journey, Father Evaristo found time and muse to talk about his job in the village, which he described as a tough mission for €250 a month. During heavy rains, the village is completely cut off for a long time. Once food was so scarce that Evaristo took the only other route out – a very dangerous route over the mountains.

Ching’ombe Mission – Sisters as a school principal and nurse

Thing that are taken for granted at home in Vienna, suddenly seemed like pure luxury to me. In the sisters’ house where I stayed, we had running water and even electricity thanks to the little turbine in the river. The rest of the village did not have this comfort. Together with Father Evaristos and Dean Frances, they sisters run the mission, which was founded by the Jesuits in 1914.

The four of us women came together for meals, which were prepared by a woman from the village. During the day I wandered around the area, and some things irritated me. When I met men, they took off their hats and women curtsied. I didn’t really know how to react to that, so I curtsied too.

Each of the sisters had a special task. Sister Margret ran the small clinic. She was mainly helped women give birth. When I visited the clinic, a group of pregnant women were sitting outside on the grass. They were cooking cassava, a type of tropical potato, which they had brought with them because patients have to provide their own food . And so they all arrive with big bags full of food for the entire stay.

7km walk to school – teachers without salary

Sister Jaqueline was in charge of the school – the number of students doubled to 400 within a year, after she took over. She made sure the children got to school and the teachers got their work done. She had cleaned up bad habits, such as tolerating a teacher who was often too drunk to teach. Why should children walk up to 7km to school for nothing, she explained.

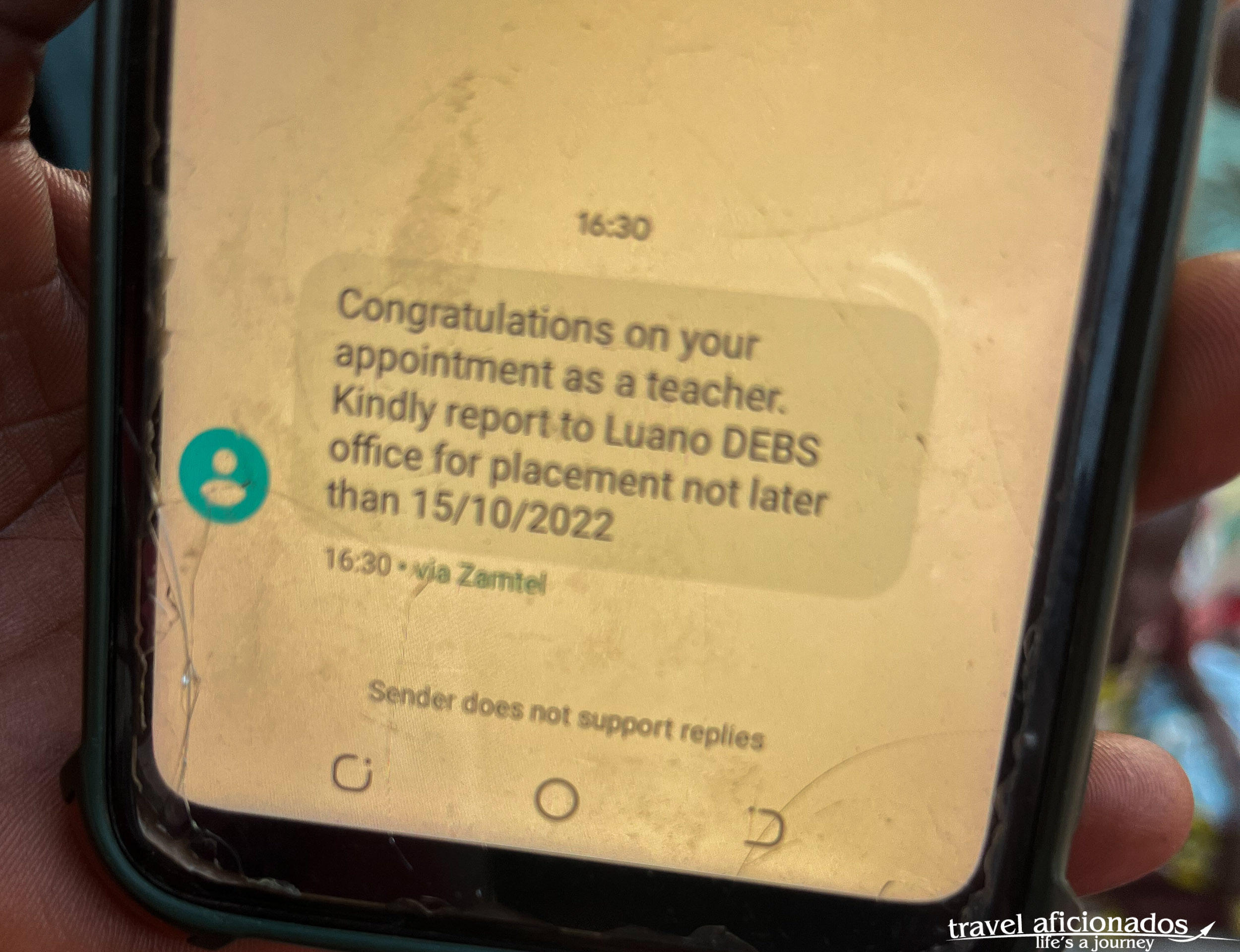

The commitment of the eleven teachers was incredible under these conditions – only three were paid, eight had been teaching as “volunteers” for a year without a salary. The house they live in had no electricity, running water or furniture; the village provided food. I happened to be present when this eight women received a text message that they were among 33.000 teachers hired by the Zambian Government that very day. Text messages are the only contact to the outside world.

https://youtu.be/J2CrcCbWViE?si=iYq8r6fDxiEEfyv7

Rural Africa close to the feudal system

The fields belong to a “chief” who often lives in the city but is the authority in the village. The “ Chilolo ” is his representative in the village. If someone needs a piece of land, the Chilolo is the person to go to. In exchange for a few goods he will provide land to work on. Once I saw the sign “Chief’s Palace”, near a village, I don’t know exactly what it looks like though. Later in the north of Zambia I got to know a “chief” personally, his huge house was next to my hostel – he drive an expensive Range Rover, sported an iPhone, must be a lucrative business.

The chief is also the judge and police, so he can punish villagers, for example by having them pull the weeds in his fields.

The Mission basically lives off the villagers – once I passed a village with Father Evaristo when chicken, peanuts were loaded on the truck- even gasoline from a canister was filled into the car.

Empowering women = empowering the village

Natuleya also runs a sewing workshop in the village. The 29 women, mostly widows and single mothers, badly need this income to keep themselves afloat.

When I visited, the women greeted me with a beautiful song and, as a sign of great honor, I was presented with a live chicken. The women proudly presented the colorful textiles that they design and sew themselves. In Austria , William sells these at various events, e.g. at Christmas markets.

Ching’ombe Sunday Mass

The day before I left, three Polish priests from an even more remote village came to the mission. Word of my nearing departure had gotten around – a free ride into the city was a rare opportunity, with gas costs at €1.5 per liter.

When I said goodbye to Ching’ombe , the village was celebrating Sunday mass. The beautiful , powerful voices of the choir – all women – filled the vibrant church . Father Evaristo held mass with the Polish priests, one of the Poles even preached in the local language, Lala. I watched him practice with Father Evaristo the night before.

Near the town Mkushi, on the main road, Father Evaristo put me on the bus to Kasama, the beginning of my epic journey by bus, train and boat to dar-es-Salam and on to Zanzibar.

Leave a Reply